Pas de biographie disponible.

Compositeur Musique additionelle Librettiste Parolier Metteur en scène Chorégraphe Producteur création Producteur version

Musical

Musique: Paroles: Charles Barras • Livret: Charles Barras • Production originale: 3 versions mentionnées

Dispo: Résumé Synopsis Commentaire Génèse Liste chansons

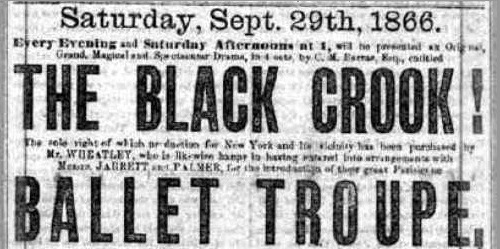

Genèse: In the summer of 1866, lower Broadway was New York's busiest thoroughfare, just as congested with traffic as it is today, but with temperamental horses and piles of manure added to the chaos of carriages and people. As post-Civil War business boomed, there was a sharp increase in the city's working and middle class population, and these growing masses of people craved entertainment. Theaters abounded in Manhattan. One of the most popular venues was Niblo’s Garden, a 3,200 seat auditorium at the corner of Broadway and Prince Streets that boasted the most well equipped stage in the city. Its manager was William Wheatley, a sometime actor and man who would invent the big-time Broadway musical. Not that he intended to invent anything. He was just trying to keep his theater in business. With the fall season set to start in a few weeks, Wheatley was stuck. He held the rights to a dull melodrama that he hoped to sweeten with lavish production values and a stack of mediocre songs by assorted composers. Salvation came in the unexpected form of a fire that destroyed New York's elegant Academy of Music, leaving promoters Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer with a costly Parisian ballet troupe and a shipload of handsome stage sets. Historians now argue about specifics, but at some point Jarrett, Palmer and Wheatley made a deal, and Broadway's first mega-hit musical began to take shape. When playwright Charles M. Barras objected to having his derivative play "cheapened" by the inclusion of musical numbers, a $1,500 bonus secured his silence. Wheatley later claimed that he spent the then-unheard of sum of $25,000 to produce The Black Crook (1866 - 474). The opening night performance on September 12 lasted a bottom-numbing five and a half hours, but the audience was too dazzled to complain. The Black Crook's tortured plot stole elements from Goethe's Faust, Weber's Der Freischutz, and several other well-known works. It told the story of evil Count Wolfenstein, who tries to win the affection of the lovely villager Amina by placing her boyfriend Rodolphe in the clutches of Hertzog, a nasty crook-backed master of black magic (hence the show's title). The ancient Hertzog stays alive by providing the Devil (Zamiel, "The Arch Fiend) with a fresh soul every New Year's Eve. While an unknowing Rodolphe is being led to this hellish fate, he selflessly saves the life of a dove, which magically turns out to be Stalacta, Fairy Queen of the Golden Realm – who was masquerading as the bird. (Are you still following this?) The grateful Queen whisks Rudolph to safety in fairyland before helping to reunite him with his beloved Amina. The Fairy Queen's army then battles the Count and his evil minions. The Count is defeated, demons drag the evil magician Hertzog into hell, and Rodolphe and Amina live happily ever after. Wheatley made sure his production offered plenty to keep theatergoer's minds off the inane plot and forgettable score. There were dazzling special effects, including a "transformation scene" that mechanically converted a rocky grotto into a fairyland throne room in full view of the audience. But the show's key draw was its underdressed female dancing chorus, choreographed in semi-classical style by David Costa. Imagine (if you dare) a hundred fleshy ballerinas in skin-colored tights singing "The March of the Amazons" while prancing about in a moonlit grotto. It sounds laughable now, but this display was the most provocative thing on any respectable stage. The troupe's prima ballerina, Marie Bonfanti, became the toast of New York. In operas, even comic operas with dialogue like The Magic Flute, the principal singers leave the dancing to the ballet troupe. In burlesque, music hall and vaudeville, there is little or no unifying story, just a series of sketches. So The Black Crook, with song and dance for everyone, was an evolutionary step, and has been called the first musical comedy. Cecil Michener Smith dissented from this view, arguing that while multiple scholars point to the show as the first popular comedy, "calling The Black Crook the first example of the theatrical genus we now call musical comedy is not only incorrect; it fails to suggest any useful assessment of the place of Jarrett and Palmer's extravaganza in the history of the popular musical theatre … but in its first form it contained almost none of the vernacular attributes of book, lyrics, music, and dancing which distinguish musical comedy." The production was a staggering five-and-a-half hours long, but despite its length, it ran for a record-breaking 474 performances and revenues exceeded a record-shattering one million dollars. The same year, The Black Domino/Between You, Me and the Post was the first show to call itself a "musical comedy." In the late 1860s, as post-Civil War business boomed, there was a sharp increase in the number of working and middle class people in New York, and these more affluent people sought entertainment. Theaters became more popular, and Niblo's Garden, which had formerly hosted opera, began to offer light comedy. The Black Crook was followed by The White Fawn (1868), Le Barbe Blue (1868) and Evangeline (1873). The production included state-of-the-art special effects, including a "transformation scene" that converted a rocky grotto into a fairyland throne room in full view of the audience. A scantily-clad female dancing chorus of 100 ballerinas in skin-colored tights, choreographed in semi-classical style by David Costa, was a big draw. It was respectable enough for the middle-class audience, but very daring and controversial enough to attract a great deal of press attention. The show's prima ballerina, Marie Bonfanti, became a star in New York. An apparently similar show from six years earlier, The Seven Sisters (1860), which also ran for a very long run of 253 performances, is now lost and forgotten. It also included special effects and scene changes. Theatre historian John Kenrick suggests that The Black Crook's greater success resulted from changes brought about by the Civil War: First, respectable women, having had to work during the war, no longer felt tied to their homes and could attend the theatre, although many did so heavily veiled. This substantially increased the potential audience for popular entertainment. Second, America's railroad system had improved during the war, making it feasible for large productions to tour.

Résumé: La comédie musicale se déroule en 1600 dans les montagnes allemandes. Le riche et démoniaque Comte Wolfenstein désire se marier avec Amina, une belle fille de village. Avec l'aide d'une intrigante, le Comte s'arrange pour que le fiancé d'Amina, Rodolphe, tombe dans les mains de Hertzog, un escroc, ancien maître de magie noire (d'où le titre). Hertzog a fait un pacte avec le Diable (Zamiel, "Le Démon Espiègle): il peut vivre à jamais s'il lui fournit une âme jeune à chaque Saint-Sylvestre. Rodolphe, destiné à cet horrible destinée, s'échappe, découvre un trésor caché et sauve une colombe. La colombe qui n'est autre que Stalacta, Reine Féerique du Royaume D'or qui prétend être un oiseau. La Reine libérée, en signe de reconnaissance, l'emmène au pays des fées et le réunit avec sa bien-aimée, Amina. Le Comte est battu, les démons traînent Hertzog en enfer, et Rodolphe et Amina vivront heureux pour toujours.

Création: 12/9/1866 - Niblo's Garden (Broadway) - représ.